On January 27th, 2019, early Sunday morning, the company was notified of a potential collision probability with another satellite that was traveling toward the firm’s pathfinder craft, Denali.

Alerts had been received in the past but these were all for “close-approaches” from other nearby objects traveling at relatively low speeds of no more than 3 meters per second, with a distance of at least 200 meters.

This particular alert was for a head-on impact at a relative speed of nearly 15 kilometers per second (33500 mph) — a velocity that would obliterate Denali, resulting in a massive amount of debris in an increasingly crowded Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) and that is a huge problem and a growing source of risk for governments and businesses.

This alert received the company’s full attention. Impact was imminent, we had to act fast. By Tuesday morning, four maneuvers were dispatched to raise Denali’s orbital altitude. The maneuvers were successful; however, the orbital trajectory of Denali and this approaching smallsat remained still too close for comfort.

As the approach neared, all waited nervously for a safe pass — at 12:22:40 p.m. on January 29, the two satellites would either collide, sending a field of debris hurtling through space, or pass each other by at a close distance. At 12:58 p.m., as Denali came over the hill, we established communication and the catastrophe had been dodged.

Although talking about space conjures images of great, empty expanses between stars, space is getting crowded. A growing cloud of space debris has been circling the Earth since the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957.

According to the European Space Agency, more than 29,000 large pieces of debris are orbiting Earth, everything from 4 inch hunks of metal to entire, defunct satellites and spent fuel canisters. Add in an estimated 670,000 pieces of metal detritus between 1 centimeter and 10 centimeters in size, an estimated 170 million flecks and particles of paint, and untold billions of frozen droplets of coolant and bits of dust smaller than a centimeter, and the operating space of LEO appears to be less of an empty expanse and more of a minefield of disabling debris.

This is not a new problem, but it is a growing one — the threat space debris poses to scientific research, telecommunications and military intelligence has been around for decades. NASA was the first space agency to issue mitigation guidelines and the United Nations put it on their agenda for action in the early 90s.

Plans to improve monitoring of current debris and reduce on-orbit collision were included in President Trump’s initial proposal of a Space Force and many experts and companies have proposed solutions to this problem — including deploying a space harpoon — but there seems to no easy answer.

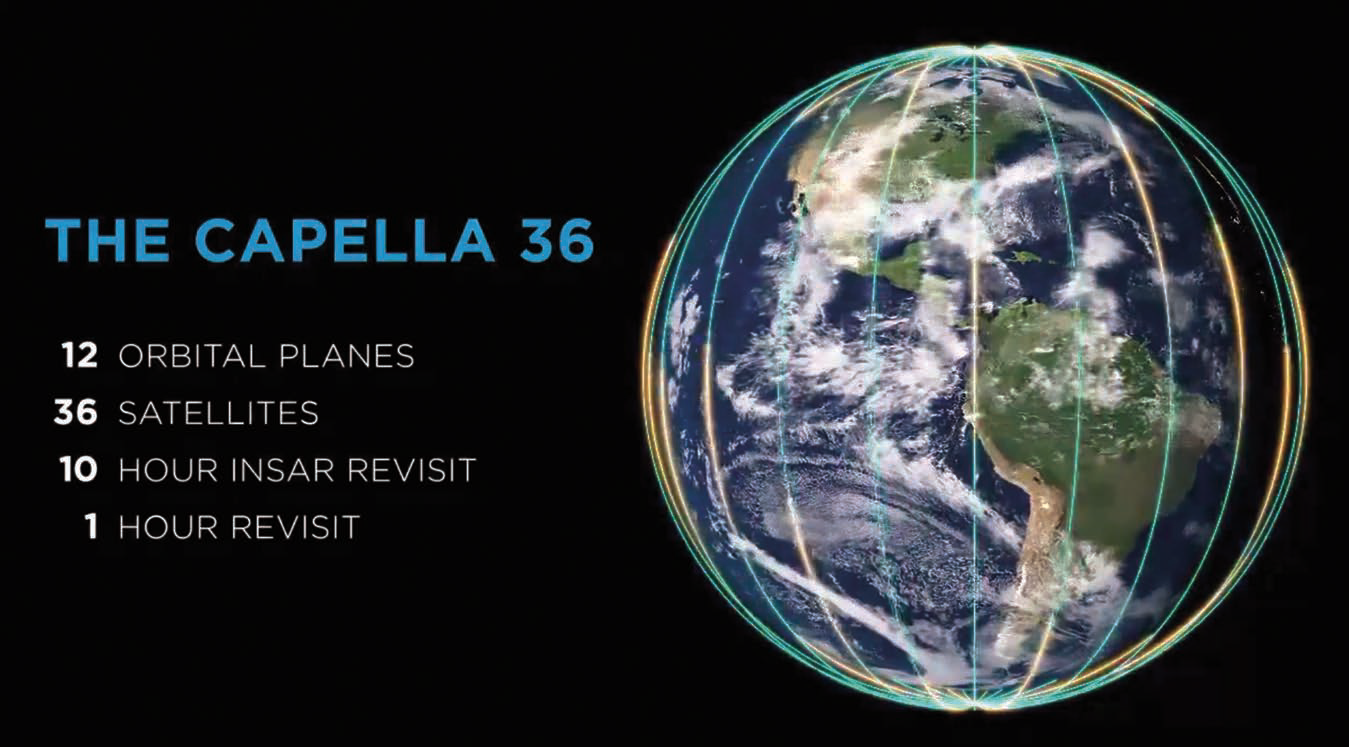

Space is an emerging frontier for commerce, with the potential to advance knowledge and communication capabilities on Earth by leaps and bounds. A company such as Capella would not have a smallsat on-orbit , let alone a feasible path toward a 12-plane, high-revisit constellation, if not for the enterprise and imagination of smart companies that possess innovative technologies and solution aspirations. With more rockets lifting off, and more satellites taking flight, the risk for hitting space debris — and creating more in the process — also increases.

The sea change in space innovation has been driving down size which, in turn, enables scale and new possibilities and applications in how space infrastructure is used to explore and monitor conditions on Earth.

Instead of the behemoth satellites of the past, which were often the size of a school bus, new models embed more power into smaller, capital-light packages. Space can now be approached faster and at lower cost, opening up tremendous opportunities for monitoring this planet, but also greater risks of collision.

With increasing activity, the time is ripe to rethink the approaches to designing, deploying, and managing assets on-orbit and to form a more collaborative approach to de-risking an increasingly crowded LEO environment.

Smarter and More Maneuverable

Most smallsats that are launched these days lack any propulsion system and capability to actively and swiftly maneuver around a potential collision. In fact, the satellite that was traveling toward Denali recently had no active means to maneuver and avoid a collision.

If Denali had been a passive satellite with no capability to maneuver itself out of harm’s way, this potentially destructive disaster could have easily turned into a major catastrophe in space with consequences far beyond Denali impacting other satellites in orbit.

There is currently no law that requires any satellite to have any maneuverability capability or collision avoidance systems. The only space debris related guideline is to bring down a satellite (either through deflection into space or burn into the atmosphere) within 25 years.

This lack of regulation might have worked okay for the last few decades; however, in the 21st century, where space is open for business, re-think debris and satellite policies and regulations is an absolute must.

Improving Coordination and Communication

Just as airplanes operate globally within the safety and flight regulations outlined by the United Nations-sprung International Civil Aviation Organization, we as a worldwide community of space pioneers and stewards could adopt a collective vision and policy structure for a safe and prosperous low Earth orbit.

To fly harmoniously, all need to play by the same rules — and we need to make sure those rules are legible and enforced, regardless of the flags anyone operates under, or the location of the launch pads.

Plan for Obsolescence

The spacecrafts of yesterday aren’t the sole source of the space junk problem. Current and future missions have a real potential to equal or surpass past debris.

Practicing space stewardship means better life-cycle management, pro-active collision avoidance and de-orbiting plans — in other words, before something goes up, there must be e a plan for how that spacecraft is going to come down and how it would maneuver to avoid a potential collision.

There’s no magic bullet to offset the space debris problem, but these three improvements together can come close to a solution. We’re living in the dawn of a golden age of satellite use and research.

To realize this potential, orbits need to be cleaned up and, when a spacecraft departs those orbits, they should be in better shape than when accessed for the benefit of future generations. This can be accomplished — if we work together.

www.capellaspace.com

Payam Banazadeh is the founder and CEO of Capella Space. He leads the overall strategy and operations of the company. Before Capella, Payam worked at the NASA Jet Propulsion Lab, where his work on two NASA missions was honored with their Mariner Award.

Payam holds a BS in Aerospace Engineering, from the University of Texas at Austin, and a MS in Business and Management from Stanford. Payam was recently named to Forbes “30 Under 30” list and is a fellow of the National Science Foundation.