The EARSC (European Association of Remote Sensing Companies) has published their first report in an ongoing series which will look at the way Earth Observation (EO) data and services contribute to developing economic value.

Previous analyses have always been top-down where the large-scale economic benefit has been assessed; for example, the Spacetec partners report of 2013 which predicts 30 billion euros of benefits. In this new approach, a single EO product is examined and the impact it makes on a chain of users is traced. In this first case, the use of satellite radar imagery to support the work of the icebreakers keeping the ports of Finland and Sweden open throughout the winter is considered.

Not many people know that “Finland is an island.” Clearly, the country is not an island in a classical sense; however, since more than 90 percent of the nation’s imports and exports travel by sea, Finland possesses one of the key characteristics of an island.

The country also has another important characteristics—all of its ports freeze over during a normal winter. Hence, the issue of sea ice is of strategic importance to the Finnish government and people.

Sweden is also seriously affected by sea ice and most of the ports on the Sea of Bothnia also freeze over. This has led to a close co-operation between the two governments to run an effective and efficient ice breaking service to keep the sea lanes open throughout the year.

Other Baltic countries face some identical problems, but none co-operate as closely as do Finland and Sweden. Presently, Estonia is interested in joining the effort, but no other Baltic States are seemingly yet ready to commit to the program. This article focuses, then, on Finland and Sweden.

The story starts with the decision taken by the Finnish government in 1971 to keep 25 major ports open throughout the year. This led to investments in ice breaking ships and the development of technology—Finland is now a world leader in ice-breaking technology.

This leadership extends to the use of satellite imagery, which was adopted in 2003. Prior to this, each ice-breaker was equipped with its own helicopter which was used to fly over the sea ice and seek out the best route. While it is a powerful tool, a helicopter has a number of disadvantages that are overcome by the use of satellite images.

First, only a limited area around the ship can be flown by a helicopter, whereas satellite images show a synoptic view of the entire Baltic. This allows routes to be plotted which are optimal directly to the port, a major benefit to the operation. Secondly, when the weather gets bad and the ice conditions are at their most changeable, helicopters cannot fly. With satellites, images can also be captured at night. Third, the cost of the imagery is now a lot less than that of helicopter operations.

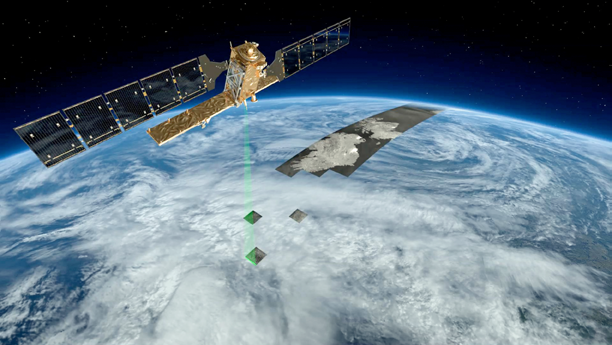

An advanced radar mission, Sentinel-1 can image Earth’s surface through clouds. Image is courtesy of the European Space Agency (ESA).

After a period of trials in the late ‘90s, the decision was taken to remove the helicopters and to rely on radar imagery. This decision also reflected that more radar satellites were operating; ERS, Envisat and Radarsat at the time and their imagery became more assured. Now, with Sentinel 1A operating and further Sentinels to follow, this is no longer a concern.

Interestingly, ice breaker captains use the imagery itself and not an ice map that is generated by the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI). The ice map is used by others, but the captains prefer to have the satellite imagery as they can “ground-truth” by looking over the side of their vessel as well as against comparisons with the conditions they know existed yesterday.

The use of the imagery allows the captains to plot shorter or more efficient routes to the port, which helps the ice breakers and the guided ships save fuel. The ships are also saving time, which translates into lower charter costs and better use of the ship to carry cargo.

Without the use of icebreakers, ships can become stuck in the ice and take many days to reach their port of destination. The opening of sea lanes (DirWays) allows operators to know the time of a ship’s arrival with more certainty. This enables ports to operate more efficiently and, in turn, the factories which are being served by the ports to better plan their production cycles.

Of course, without the icebreakers, the factories would probably not be able to operate at all. At best, they would be working eight or nine months of the year, so the impact of the ice breaking services on the factories and on the local economy is a boon.

The impact on the factories and the local economy is significant. Timber, paper and steel are the main industries in this area of Finland and Sweden. There are no refineries, but there are depots of petroleum products which are shipped from southern Finland. Just-in-time production methods require confidence in both the arrival time of raw materials and what the possibility is to ship finished products.

Delays to shipping can have significant impacts. In example, a paper company had to fly out newsprint during a particularly hard winter at greater cost or risk losing their contract with a European newspaper.

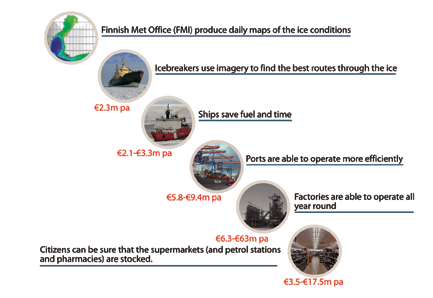

How much is all of this worth? The methodology which The EARSC is testing takes each step in the value chain and, through an understanding of what is happening, is able to derive methods to analyze the benefits.

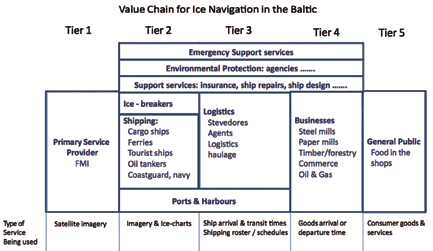

Figure 1.

For the case of winter navigation in the Baltic, the organization was able to do so with the results as shown in Figure 1 on the following page. This shows each step in the value chain and the economic benefit that can be calculated for each step.

The steps are at least partly defined by the type of information that is relevant and the changes between each one. For the ice breakers, the SAR image is used; for ships, they use the routes designated by waypoints defined by the ice breakers; for the ports, the time of the ship’s arrival is the important criteria; for the factory, they are concerned with the arrival or departure of their goods. These are the parameters used to assess the value as shown in Figure 2.

The overall benefit is quite surprising. Lacking any prior analysis of the impact of the ice breaking services on the Finnish economy forced the EARSC to develop a new model and to make a number of assumptions. None of these conservative assumptions have been challenged. Nevertheless, EARSC analysis reveals an overall economic benefit of between 24 and 116 million euros per annum. The range is due to the cascading effect of using ranges of values for certain steps in the value chain.

At the outset EARSC considered that each value chain derived from a single EO product would demonstrate value of several 100,000 euros and perhaps up to 1 million euros.

Figure 2.

The impact of EO is touching every citizen living in Finland and especially those living on the Sea of Bothnia. With greater certainty of the arrival of the ships, citizens are employed throughout the year in working factories and can be more assured of having fuel to heat homes and power their cars as well as being able to visit fully stocked supermarkets and pharmacies.

How much are they prepared to pay for these necessities? The EARSC make a simple estimate in the report, however to know an actual cost factor and to validate further assumptions will require a much larger study.

The EARSC shows how the images generated by satellites are benefiting the citizens whose taxes have helped to pay for their on orbit capabilities. The level of economic benefit from this one service is quite high. The benefits extend from the cost of operating ships through to the local economy, including the local citizens. Indeed, satellites touch the everyday lives of all of us.

For additional information regarding this organization, please visit: earsc.org